MIT’s campus links more than 200 buildings that comprise 13.9 million square feet, with 8.3 million square feet dedicated to academic purposes—classrooms, labs, libraries, offices, and more—and 3.3 million in residences.

Keeping these buildings safe and operational is no small feat—and heating and cooling is one of the most critical functions that MIT’s Facilities teams take on each day. Consequently, it’s also one of the biggest areas of impact that Campus Climate Action needs to address. Why?

Today’s campus-wide building management systems simply aren’t built to respond efficiently to the unique needs of thousands of different spaces.

For example, if a classroom is only in use for a couple of hours each day, does it need to be held at a consistent, people-friendly temperature? Do certain labs need to be maintained at a specific temperature—yet within a building that doesn’t need to be heated or cooled to that extent in every space? Does a building mostly in use during standard working hours need to accommodate users who like to work late or come in early?

Add in the unpredictability and relative extremes of New England’s seasons, the steadily increasing temperature levels we’re seeing as a planet, and the preferences of several thousand unique people, and you’ve got yourself quite a set of variables.

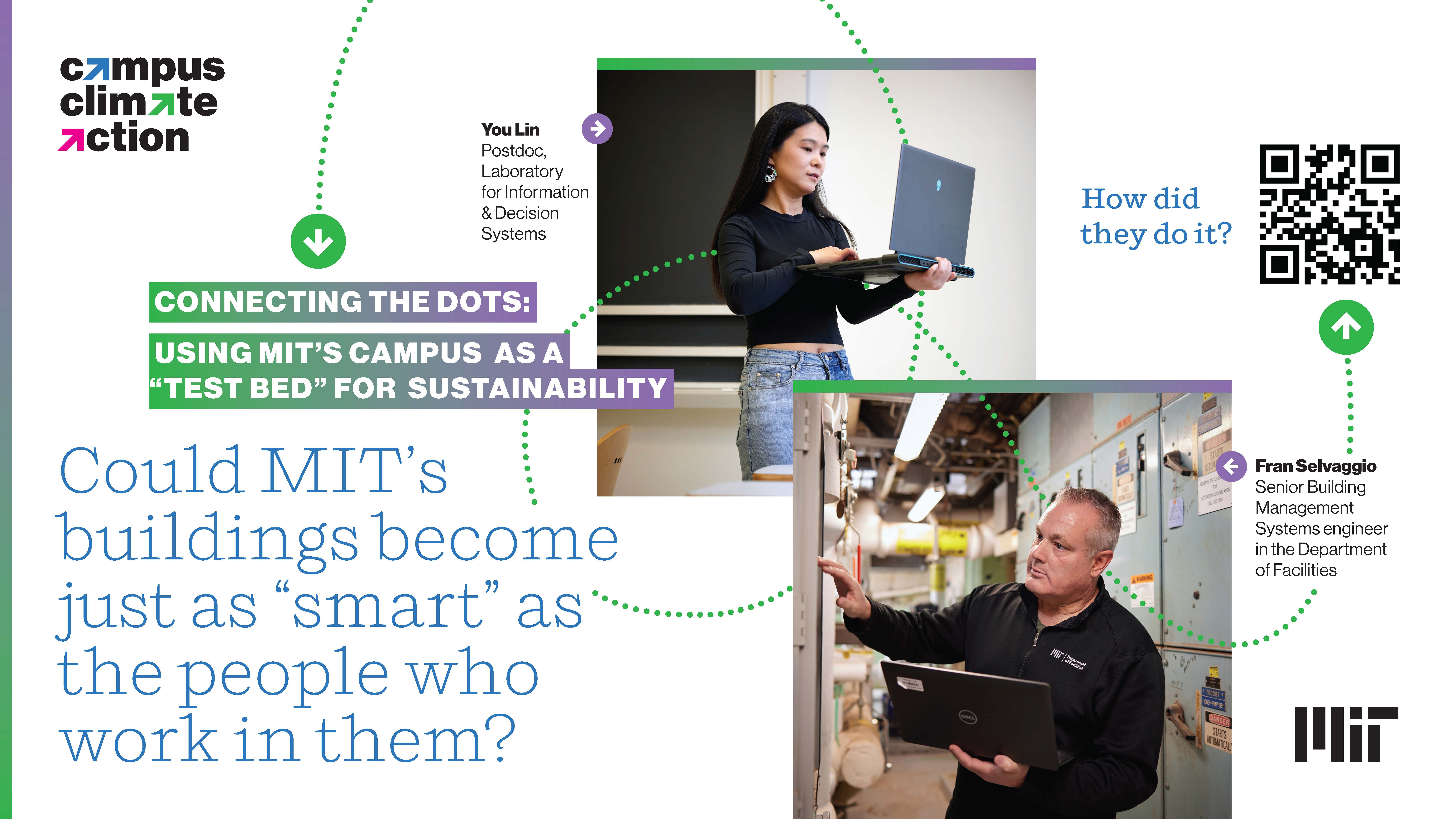

The result? Plenty of inefficiency and wasted resources—and a climate impact in dire need of mitigation. As Jeremy Gregory, executive director of the MIT Climate and Sustainability Consortium explains, “Our buildings are the biggest part of our carbon footprint. The inefficiencies there are a paramount problem to solve—and if we’re going to use the campus as a ‘test bed’ for change, we do well to start tackling our biggest hurdles now.”

The research-driven response

Chances are you’ve heard a lot about artificial intelligence (AI)… for better or for worse. While AI’s capacity to write a Hollywood screenplay or create a work of art for MOMA is up for debate, AI can have a powerful impact on our capacity to balance energy needs in complex environments.

If you have a “smart” thermostat in your home, you’ve experienced how sensors in different parts of your space gauge heating and cooling according to the weather outside, the rooms you’re occupying (or not), what you’re doing in those rooms at what times of day, and your personal preferences.

The smart part: your thermostat will either self-adjust to reflect those preferences or will respond according to the way you’ve programmed it to act… ideally in a seamless manner, while you’re comfortably living your life.

Joe Higgins, Vice President for Campus Services and Stewardship, originally pitched the idea of using AI to support campus energy efficiency to students at the 2019 MIT Energy Hack. A fresh challenge was issued to MIT researchers and Facilities teams to collaborate on AI implementation within MIT’s plant—and the AI Pilot Project was born.

As Les Norford, a professor of architecture at MIT, explains, “What works in your house is possible because of the scale—a few sensors across a few rooms have many data points, but nothing like a whole campus. MIT has more buildings, more variables, and more people who demand a certain level of comfort in their environment. But sooner than later, you must tend to your own business!”

Audun Botterud, principal research scientist for the Laboratory for Information and Decision Systems, conducts research that addresses the need for a decarbonized energy grid, from energy market interactions to designing batteries that store energy more efficiently, and at a greater volume.

Botterud’s focus makes him the perfect partner to work with a machine learning algorithm that would use data from a set of classroom spaces—for now, all in Building 66. The different needs of each classroom presented an appropriately complex environment to gauge how heating and cooling could be optimized in the face of external weather influences, occupancy needs, and the presence of different heating zones, often a wall or two away.

“This was my first time being involved in a project like this at MIT, and it’s great to be working on something very much at the applied end of the research spectrum,” said Botterud. “This is exactly how we should be using the campus as a ‘test bed’—to pioneer new solutions that we can build out across campus, and then share with the world.”

For Fran Selvaggio, senior building management systems engineer in the Department of Facilities, the first challenge was to ensure the Building Management System was ready before the AI variable was added into the mix. “Our systems wouldn’t functionally interact effectively with AI unless everything was in excellent shape—which is why the first step in innovation often begins with making sure your current systems are optimized.”

As MIT continues to learn from the AI pilot in Building 66, the plan is to scale out further and introduce more buildings into the pilot, and give the AI algorithm more data to work from to optimize MIT’s efficiency across its physical plant.

To learn more about MIT’s Fast Forward commitments, start here. To learn about MIT’s Campus Climate Action-specific efforts, head here. To view the MIT News version of this story, visit here.